Table of contents

Nebula Genomics DNA Report for Obesity

Is obesity genetic? We created a DNA report based on a study that attempted to answer this question. Below you can see a SAMPLE DNA report. To get your personalized DNA report, purchase our Whole Genome Sequencing!

| This information has been updated to reflect recent scientific research as of June 2021. |

What is Obesity?

Obesity is a complex disease that is most often presented as excess body fat. Although most people recognize it as a cosmetic condition, it often has serious pathological effects and medical consequences, such as an increased risk of heart disease and type 2 diabetes. It can also lead to adipose tissue inflammation. Did you know you can test inflammation markers at home? Learn more in our article about at home inflammation tests.

According to the World Health Organization, WHO, obesity is present in people with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m² or more. In this context, a distinction is made between three degrees of severity, differentiated from each other by the BMI. Indicators for the proportion of body fat and its distribution are the abdominal circumference and the waist-hip ratio.

The condition is often a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The decisive factor for this risk is not the BMI but the fat distribution pattern. Fat mass deposited in the abdomen and on the internal organs has a particularly detrimental effect (so-called apple type). This internal abdominal fat has a particularly unfavorable impact on fat and carbohydrate metabolism (sugar metabolism) and is considered a significant indicator of metabolic syndrome, leading to dyslipidemia and diabetes. The more hip- and thigh-emphasized fat distribution (so-called pear type) is considered to be lower risk.

Is Obesity Genetic?

The genetic contribution of obesity is often a topic of debate. This is because the steep rise in cases cannot be attributed to genes alone. However, many people have genetic predispositions that affect how their body responds to risk factors such as inactivity and poor diet. Genes may also increase hunger or food intake, leading to obesity, especially if additional genetic factors predispose a person to conditions like slow metabolism.

No single gene has been linked to the condition. It is generally believed that a complex combination of genetic interactions and environmental factors ultimately leads to the condition.

The most common gene cited as being involved in genetic obesity is the MC4R gene that encodes the melanocortin 4 receptor. Its popularity is mainly based on a 2008 research paper in Nature Genetics that cited mutations in this gene as a contributing factor to having a BMI greater than 30. Mutations seem to cause extreme hunger, which ultimately leads to overeating.

In 2007, an association of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene region and risk of obesity was identified, making this locus the first to claim a genetic basis for the condition.

Between 2006 and 2013, over 50 genes were associated with the condition, although most were found to have minimal effects, especially compared to environmental factors. The more popular use of genome-wide association studies has led to even more genes being identified since. Technically, any genetic variant that affects signals that guide food intake or how food is metabolized in the body may be linked with the condition.

In rare cases, gene variants can directly lead to obesity. This only occurs in diseases such as monogenic obesity, Bardet-Biedl syndrome, and Prader-Willi syndrome.

While some genetic factors may predispose an individual to obesity, whether a person becomes obese is strongly correlated to behavior and lifestyle choices. These behaviors tend to be shared by family members, which can make it seem like heredity plays a role. Family history may contribute, but mostly by associated factors and less by genetics. Most people who are predisposed can avoid the disorder through healthy eating and exercise.

Current Research on Genetic Obesity

There have been many types of research that support genetic obesity.

According to a 2021 article by the Harvard School of Public Health, called Genes Are Not Destiny, research showed that while obesity may be linked to some genes, various environmental factors more strongly influence the extent they play in making a person obese.

The article stated that genes affect every part of human psychology, development, and adaptation. And obesity is no exception. However, while most genetic conditions are easily passed to relatives, genetic obesity depends on life experiences. It stated that fried and fatty foods could interact with genes related to obesity and increase the risk of obesity in offspring who are genetically predisposed compared to those who do not expose themselves to these risks.

The study showed that many gene interactions must be present to contribute to obesity and then these genes only carry small risks. Most people do not end up overweight if they lead a healthy lifestyle and eat healthier food that promotes weight management, as this will successfully counteract obese genes’ effects.

Another gene that has been associated with obesity is the fat mass and obesity-associated gene (FTO gene) which codes for the FTO protein. The relationship of the FTO gene with obesity was confirmed through single nucleotide proteins SNPs. While there is no clear explanation of the mechanism through which FTOs influence obesity, people with reduced FTO activity have shown lower fat cell lipolysis (causing increased body fat accumulation), which shows that the FTO gene somehow affects body fat metabolism.

Another 2011 research article titled Genetics Of Obesity: What We Learned, showed that candidate gene and genome-wide association studies led to the discovery of nine loci involved in Mendelian forms of obesity and 58 loci contributing to polygenic obesity.

Another article by the Centers For Disease Control And Prevention in 2013 stated that overweight and obesity resulted from energy imbalance due to eating more calories than is needed by the body. It also stated that many genes play a contributing role in obesity, but they have very little impact on their own except they are aided by an unhealthy lifestyle. It stated that the MC4R was the most commonly implicated gene and is responsible for encoding the melanocortin 4 receptor.

You can check out this review that covers obesity education in schools of medicine around the world.

Epidemiology

According to the WHO, the worldwide prevalence of obesity has nearly tripled since 1975. Adult obesity is widely believed to be a public health emergency. In 2016, over 1.9 billion adults were overweight. Of these, over 650 million were obese. This is equivalent to 39% of all adults being overweight and 13% being obese adults.

Over 340 million children and adolescents aged 5-19 were overweight or obese in 2016. These numbers rose dramatically from just 4% in 1975 to just over 18% in 2016. The increase was the same in both males and females.

Globally there are more people who are obese than underweight in every region except parts of sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

Symptoms

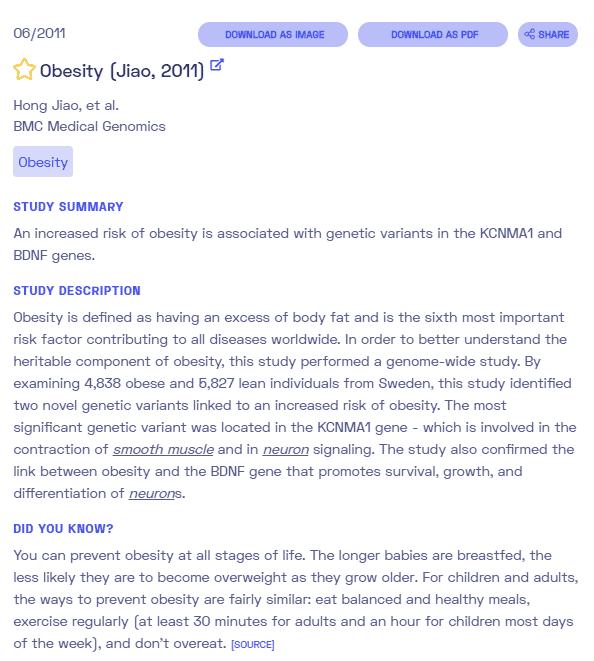

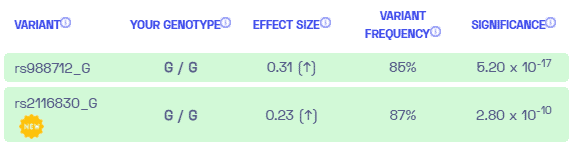

The main symptom of the condition is when a person has a BMI greater than 30. The various BMI categories for adults defined by the WHO in BMI (kg/m²) are:

- Underweight: below 18.5

- Normal weight: 18.5-24.9

- Overweight: 25-29.9

- Obesity: 30-34.9

- Severe obesity: 35-39.9

- Morbid obesity: (also known as Class III obesity): ≥ 40

Different definitions exist for children under the age of 18 and are based on Child Growth Standards.

In most instances, BMI is correlated with body fat. However, it does not account for muscle mass. Therefore, some individuals with large muscle content, such as professional athletes, may have a BMI in the obese range even though they do not have excess body fat.

Other medical consequences

Raised BMI is a significant risk factor for other diseases and health problems such as:

- Diabetes

- Cardiovascular diseases (especially heart disease and stroke)

- Musculoskeletal disorders (mainly osteoarthritis)

- Some cancers (including ovarian, endometrial, breast, prostate, liver, gallbladder, colon, and kidney).

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- High LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, or high levels of triglycerides (Dyslipidemia)

- Sleep apnea and breathing problems

- Low quality of life

- Mental illness such as clinical depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders

- Body pain and difficulty with physical functioning

More information can be found in Clinical Problems Caused by Obesity, written by Ioannis Kyrou, M.D., PhD, Harpal S Randeva, MD, PhD, FRCP, Constantine Tsigos, MD, PHD, Grigorios Kaltsas, MD, FRCP, and Martin O Weickert, MD, FRCP.

Childhood obesity is associated with a higher chance of problems in adulthood like obesity, premature death, and disability. In addition, obese children may also experience difficulty breathing, increased risk of fractures, hypertension, early signs of cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, and psychological effects.

Causes

Obesity is complex and can be attributed to many different factors, including environmental, lifestyle choices, and genetics. One of the most important factors in preventing excess weight gain is balancing the number of calories consumed through food and drink with the number of calories lost due to physical activity.

Resources to assist with making healthy eating and physical activity choices are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website.

Lifestyle factors

Some behaviors that can contribute to obesity include lack of physical activity, unhealthy dietary patterns, and medication use. Reducing these factors is often effective in maintaining a healthy weight.

Community environment

The community environment is an important factor that contributes to obesity, especially in industrialized countries. Such environmental factors may include a lack of safe places to exercise, food desserts that make healthy foods inaccessible, and lack of proper education tools in schools.

Unfortunately, an individual has typically little control over their environmental factors, and they tend to affect the most vulnerable communities, especially those primarily of black and other diverse populations.

Diseases and medications

Some medical conditions, such as Cushing’s disease and polycystic ovary syndrome, increase the risk of obesity. Likewise, medications such as steroids and antidepressants may cause weight gain. A medical professional leading your treatment will provide medical advice to help you deal with weight gain in these situations.

Diagnosis

Generally, the condition is diagnosed through a physical examination and calculation of BMI. A BMI over 30 is considered obese. To calculate BMI, you divide your weight in kilograms (kg) by your height in meters squared (m2). There are also plenty of online calculators that will perform the math for you if you provide your height and weight in any measurement, such as the one from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Other tests the doctor may perform will determine if an underlying cause or condition is the culprit for obesity. They may ask about things such as weight history, exercise level, eating habits, stress, and medications. They may also check vital signs such as heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature.

Measuring your weight circumference helps determine your risk of heart disease. Typically, more fat stored around the waist indicates a higher risk than when fat is stored in the thighs or buttocks. Women with a waist measurement of more than 35 inches (89 cm) and men with a waist measurement of more than 40 inches (102 cm) are typically more at risk.

Waist circumference is an important predictor of heart disease. Pixabay.

Checking for other conditions that may be causing the obesity may be performed to help guide treatment. High blood pressure and diabetes are often co-morbid conditions that can be easily tested for. Blood tests may be performed to check for cholesterol levels, liver function, and thyroid function.

Treatment

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases provides some helpful treatment information on their website. Several systematic reviews indicate that early prevention strategies are important components for successful treatment.

Lifestyle changes

Lifestyle changes through weight management programs that include diet and exercise are the most commonly recommended treatment option. Diet may consist of consuming more low-calorie foods (fruits, vegetables, whole grain) while avoiding excess calories (many sodas and fried foods are in this category). Moderate exercise is generally recommended for at least around 3 hours per week or 30 minutes each day.

This is often the most effective and least invasive for the majority of patients. Digital devices such as fitness watches and phone apps are usually recommended to help track progress.

Experts recommend losing 5 to 10 percent of your body weight within the first six months of treatment. This means that if you start the program at 200 pounds, you should aim to lose at least 10 pounds in 6 months. Eating fewer calories and exercising regularly are key to this approach.

Some patients benefit from formal weight management programs. In these instances, the patient works with professional coaches to form weight goals and plans. These coaches often have an accountability partner who can also share successes, encourage through setbacks, and help patients adjust plans.

Other types of personal help may include counseling and support groups. You may be particularly interested in online resources, including blogs, many of which are written by MD Ph.D. scientists.

Medication

When diet and exercise are not enough or weight returns quickly, your doctor may prescribe weight loss medications as a treatment of obesity. These medications work by preventing hunger and increasing the feeling of fullness, resulting in the consumption of fewer calories. Your doctor is more likely to prescribe these types of medications if your BMI is over 30 and if you have obesity-related conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure, or sleep apnea.

Some FDA-approved medications include:

- Orlistat (Alli, Xenical)

- Phentermine and topiramate (Qsymia)

- Bupropion and naltrexone (Contrave)

- Liraglutide (Saxenda, Victoza)

It’s important to remember that these medications only work if used as a complement, not a replacement, to diet and exercise.

Surgery

Surgery is often the last resort to treat obesity, and it is not recommended very often. Typically, it is reserved for patients who have severe obesity (over 40), who have tried other options and have serious health conditions due to obesity. Weight loss surgery, called bariatric surgery, works by limiting the amount of food you can comfortably eat or decreasing the amount of food that can be absorbed. It often results in long-term lifestyle changes and comes with risks.

Although some patients lose weight up to 35% of excess fat from these surgeries, it is not guaranteed to work. It also doesn’t ensure that patients will keep the weight off. After surgery, it is usually necessary to maintain healthy eating and exercise habits or risk that the weight will return.

Some examples of surgery include:

- Gastric bypass surgery

- Adjustable gastric banding

- Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch

- Gastric sleeve

More resources can be found on the website of the United States Department of Health and Human Services.

If you liked this article, you should check out our other posts in the Nebula Research Library!

August 3, 2022