Edited by Christina Swords, Ph.D.

A genetic look at lefties

If spiral-bound notebooks, scissors, and can openers are your mortal enemies, than chances are you are left-handed. Yes, lefties understand — often from painful first-hand experience, pardon the pun — the struggles of living in a world designed for right-handers. While only about 10 percent of the population is left-handed, they count among their ranks some highly distinguished folks. For example, six of the previous 12 U.S. presidents were (or are) southpaws. Also, left-handers account for a larger than expected share of Nobel Prize winners. And Oprah, Bill Gates, Jimi Hendrix, Babe Ruth, Marie Curie, and Einstein — all lefties.

While there is a growing body of research that suggests left-handers often outperform right-handers in various ways (verbal skills, memory, and yes, even video games, to name a few), strikingly little is known about why and how this preference for the left hand over the right develops in the first place.

Now, a new study published in the journal Brain by a team of University of Oxford researchers offers a tantalizing glimpse of some of the genes and genetic differences that contribute to left-handedness. Their findings also shed light on the variations in brain structure that correlate with these genes, offering some early clues about how brain development and function might unfold differently in lefties compared to righties.

Handedness is just one of many traits that make us who we are. From height to heart disease risk, it is now possible to reveal thousands of genetic variations that contribute to your own unique biology through the power of genome sequencing and genome-wide association studies (or GWAS). At Nebula Genomics, we continually monitor the scientific literature to bring you the latest insights in these areas. This week, the handedness study is the newest addition to the Nebula Research Library.

Previous studies of twins hinted that handedness is influenced by genes, but also that genes are only part of the story. About a quarter of the variability in the trait is due to genetics; the rest is controlled by non-genetic factors. Although some studies have found a higher proportion of left-handedness among individuals with schizophrenia, prior to the new study there had been no genes definitively linked with the trait.

To uncover genetic variations associated with handedness, the Oxford University researchers scoured the genomes of some 400,000 people from the UK Biobank, including more than 38,000 lefties. They found four regions of the genome associated with left-handedness, three of which include genes that influence brain development and structure. (One of these regions includes a gene that contributes to the scaffolding that supports the cells in the body — a structure known as the cytoskeleton.)

In a second set of analyses, the team examined detailed brain images from roughly 10,000 participants. They found that the genetic variants associated with left-handedness were also correlated with differences in brain structure and activity, particularly in regions involved in language.

“This raises the intriguing possibility for future research that left-handers might have an advantage when it comes to performing verbal tasks, but it must be remembered that these differences were only seen as averages over very large numbers of people and not all left-handers will be similar,”

said Akira Wiberg, a Medical Research Council fellow at the University of Oxford and lead author on the new study.

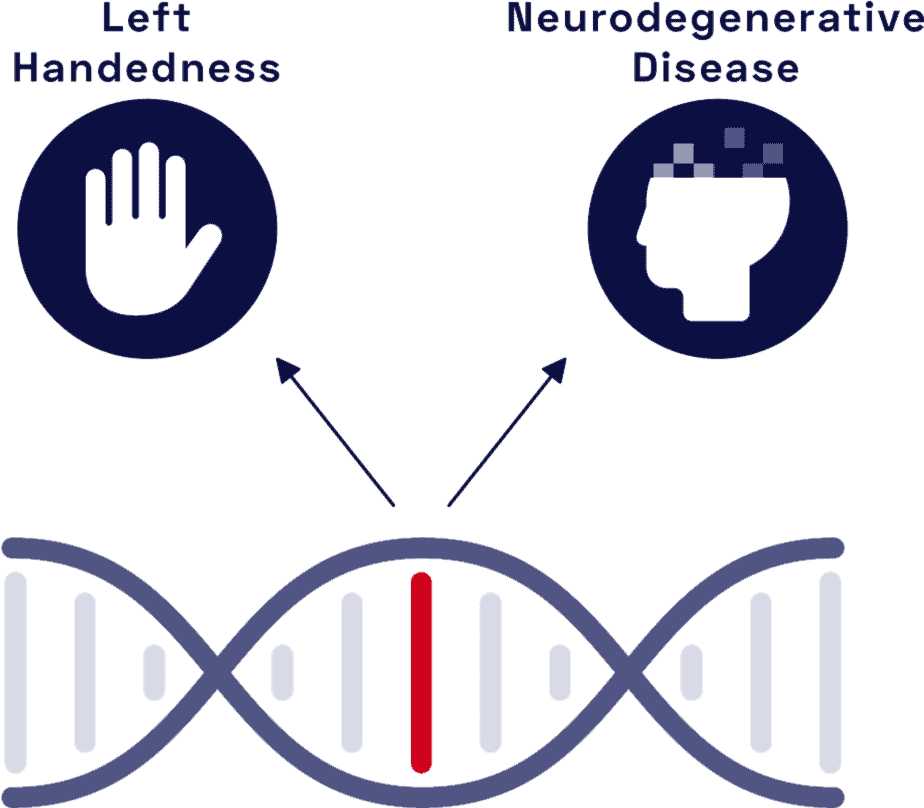

Wiberg and her colleagues also uncovered connections between the genetic regions associated with left-handedness and the risk of certain neuropsychiatric diseases, including schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease. But the connections are relatively weak and will require further studies to confirm. Nevertheless, such efforts could lead to a deeper understanding of the brain, both its normal biology and disease.

It is important to recognize that the genetic variants identified by the Oxford team account for a relatively small portion of the genes involved in handedness — just 1 percent — which means a sizeable piece remains unexplored. And since the study was conducted using samples from the UK Biobank, it represents a tiny fraction of the global population.

Nevertheless, the new findings help underscore the biological nature handedness. In many cultures, left-handedness has long been considered undesirable — even ominous or evil.

“Indeed, this is reflected in the words for left and right in many languages,” said Dominic Furniss, a hand surgeon at the University of Oxford and co-senior author of the study. “For example, in English ‘right’ also means correct or proper; in French ‘gauche’ means both left and clumsy.”

He added, “Here we have demonstrated that left-handedness is a consequence of the developmental biology of the brain, in part driven by the complex interplay of many genes. It is part of the rich tapestry of what makes us human.”

To learn more about the genetic variants mentioned here, check out the Nebula Research Library. You can discover which variants are associated with a particular trait or disease — and whether or not you carry them in your own genome. You’ll also find a summary of the relevant research associated with those variants as well as other resources you can explore to dig even deeper into the latest genomic findings.

Here at Nebula, it’s our mission to provide a private and secure way to learn about what your genes say about your traits and ancestry. That means you can embrace the age of personal genomics without risking the privacy of your most personal and unique possession — your DNA.

Order your kit today to begin your journey toward owning your genetic data and better understanding your genes.